by Zuzana Schwidrowski, Director of Gender, Poverty and Social Policy Division and Omolola Mary Lipede, Fellow

Africa’s future prosperity needs its girls…

Africa is home to approximately 160 million adolescent girls aged 10 to 19[1]. They embody the energy, creativity, and potential of the continent. It is undeniable that The Africa We Want, as envisioned in the African Union’s Agenda 2063, will not be realized without the full participation of this group which represents a key component of the continent’s current and future workforce. Yet one of the most persistent obstacles to realizing this vision is the prevalence of child marriage and its negative impact on Africa’s productive capacities. Child marriage is among the most underestimated structural constraints on Africa’s capacity to harness its demographic dividend.

…yet millions are being left behind

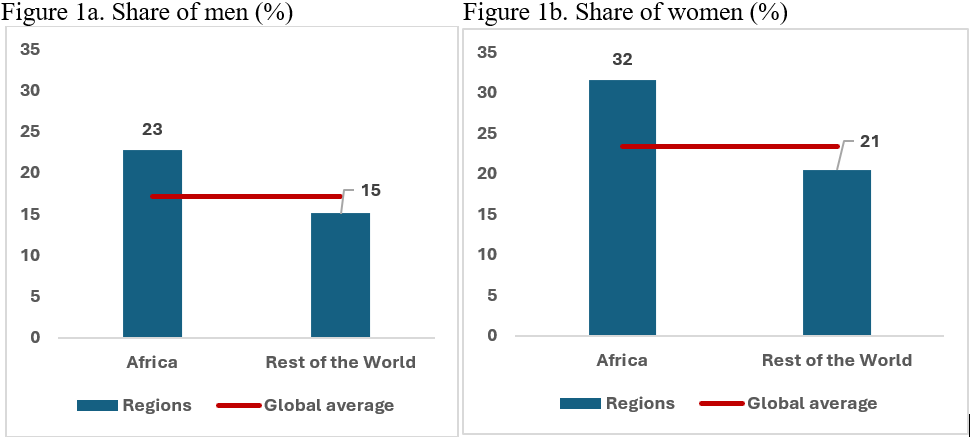

The statistics paint a concerning picture. According to the World Bank, four out of ten girls aged 15 to 19 in Africa (excluding North Africa) are not in school and not working, or are married or have children, compared to just slightly above one out of ten boys.[2] On average, nearly one-third (32 percent) of young women (ages 15–24) are not in education, employment, or training (NEET), compared with 23 percent of boys in that age range (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Share of Africa’s youth not in employment, education, or training (NEET), by gender

(percent of population 15 – 24)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the World Bank database.

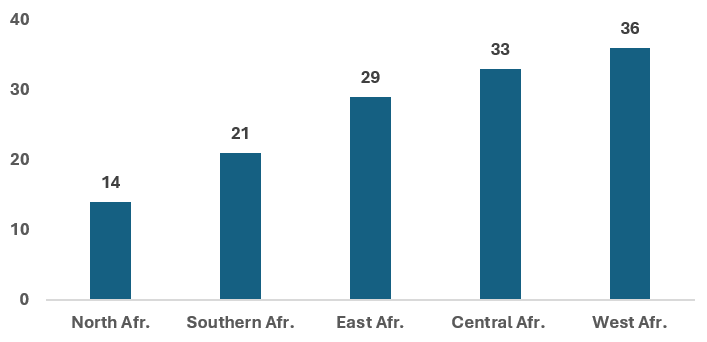

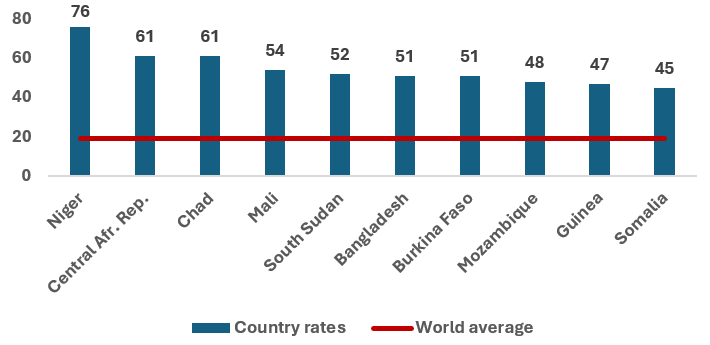

In Africa, 130 million women and girls were married before their 18th birthday, the highest incidence of globally (UNICEF, 2025). The prevalence of child marriage varies across the continent. Central and West Africa bear a disproportionate share of the global burden. But even North Africa, with the lowest yet significant rate of child marriages, shows that this harmful practice persists across the continent (Figure 2). Moreover, nine out of ten countries with the highest incidence of child marriage are in Africa (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Prevalence of child marriage across Africa’s regions

(% of girls married before the age of 18)

Source: UNICEF global database, 2025.

Figure 3. Countries with the highest rates of child marriage globally

(% of girls married before the age of 18)

Source: UNICEF Child Marriage Portal, Prevalence and burden of child marriage.

The data reflect the most recent available information for the period 2016-2023.

…and economic costs are staggering

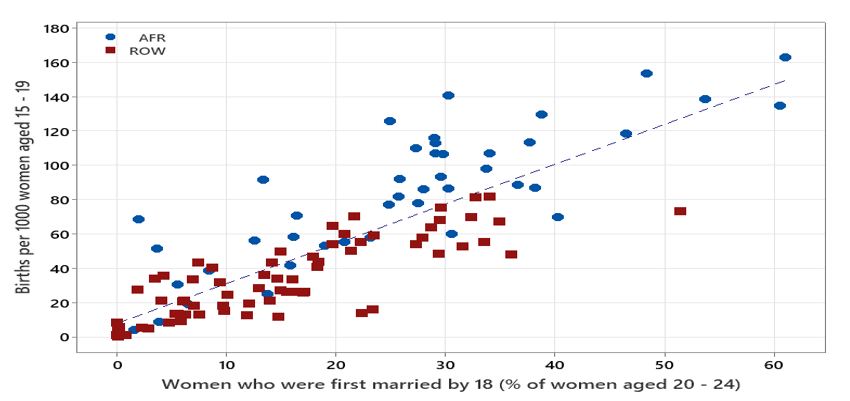

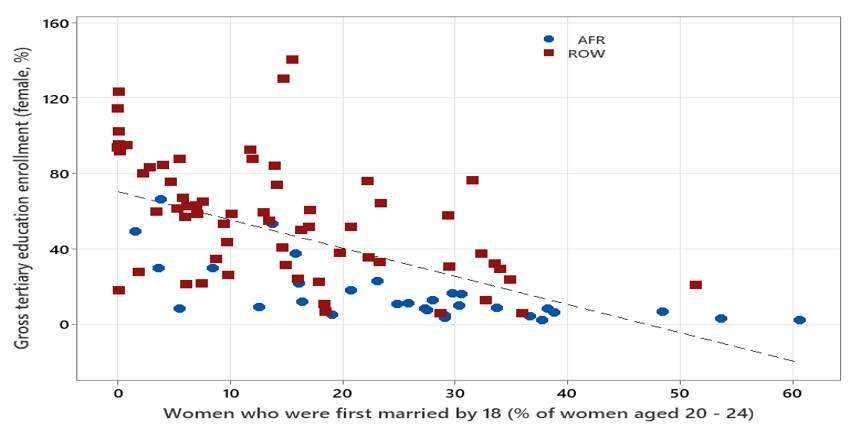

Child marriage is most frequently portrayed as a human rights violation or a social and health issue. And indeed, complications from pregnancy and childbirth remain a leading cause of death for adolescent girls. These tragic and most visible aspects, however, are only part of the story. Less visibly, but most frequently, child marriages are associated with early pregnancies and effectively exclude girls from education and formal economic participation at the very stage when investments in skills and learning yield the highest returns (Figures 4 and 5). Besides limiting individual futures, this practice thus has major economic implications for African countries and regions.

Figure 4. Prevalence of child marriages and adolescent fertility rates

Source: Authors, based on the World Bank Gender Portal.

Note: The graphs include both African (AFR) and non-African countries (ROW).

Figure 5. Prevalence of child marriages and female tertiary enrolment

(% of female population 19 – 24)

Source: Authors, based on the World Bank Gender Portal.

For African countries, as for some other developing countries, child marriage is a major unaddressed economic distortion. It distorts human capital accumulation and labor allocation, with economy-wide consequences for productivity and growth. More specifically:

- Child marriage truncates education, limits skills acquisition, and impedes women’s participation in the formal labor markets

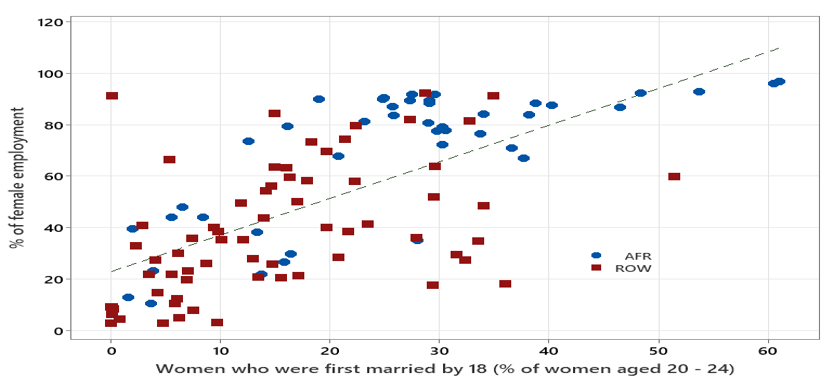

- Girls who marry early are far more likely to enter unpaid care work or low-productivity informal activities, with limited prospects for upward social mobility (Figure 6).

- Child marriage limits girls’ full integration into society by depriving them of their rights, identities, and agency. It creates dependency and stalls leadership potential.

Figure 6. Prevalence of child marriages and female vulnerable employment

(percent of total female employment)

Source: Authors, based on the World Bank Gender Portal.

The implications for Africa’s labor markets are particularly severe. Productive structural transformation requires a workforce that can move from low-productivity activities into higher value-added sectors, including manufacturing, modern services, and the digital economy. When girls’ education and skills acquisition are cut short, the supply of skilled workers for these sectors is reduced. In turn, incentives of entrepreneurs to create and grow productive firms are curtailed. At the macro level, productivity growth, job creation in the formal sector, and diversification into high value-adding activities are diminished.

Economic costs of child marriages persist across generations. The practice is closely associated with early and high fertility, increased maternal morbidity and mortality, and poorer health and educational outcomes for children. If unaddressed, these social outcomes lead to lower human capital (educational attainments and health) of the next generation, thus reducing labor productivity and innovation. Over time, they result in a persistent barrier to achieving fiscal sustainability, regional integration and inclusive growth.

These dynamics hamper Africa’s chances to seize demographic dividend. While the continent’s growing working-age population is viewed as a potential source of accelerated growth if accompanied by adequate investments in health, education, and job creation, child marriages are accompanied by reduced female employment in the formal sector (Figure 6). Subsequently, productivity gains fall below potential and demographic opportunity risks becoming a demographic burden.

Despite the negative macroeconomic implications, child marriage is not included in the mainstream economic frameworks and discussions that inform macroeconomic planning and policies in Africa. It is typically addressed through social or legal interventions, while macroeconomic strategies, industrial policies, and fiscal frameworks proceed as if these aspects of human capital constraints were exogenous. Such disconnect results in systematic underinvestment in one of the most binding constraints on Africa’s productive capacities.

Policymakers and the population at large need to rethink child marriage

From an economic perspective, the case for investing in girls is compelling. Analysis consistently shows that investments in girls’ education and health yield high returns, raising lifetime earnings, boosting productivity. Closing gender gaps in education, employment, and decision-making could add up to a trillion USD to Africa’s GDP in 2043.[3] Estimates also suggest that every dollar invested in adolescent girls’ health, education and empowerment can generate multiple dollar economic returns over time.

Translating evidence into effective policies will require a shift in approach -- a one where ending child marriage is seen as a core component of Africa’s economic strategy. Indicators on adolescent girls’ education, employment, and unpaid care burdens should thus become an integral part of macroeconomic frameworks, labor market projections, and assessments of productive capacity. Against this background, addressing the child marriage issue in Africa is a matter of economic necessity, given that successful Africa’s transformation requires unlocking the full productive potential of its population. This, in turn, demands sustained investment in girls as economic actors and not merely as beneficiaries of social programs.

Africa must finance Africa's girls, and measures such as strengthened domestic resource mobilization, gender-responsive budgeting, and gender bonds could go a long way in this regard. Moreover, policymakers should view public spending aimed at reducing child marriages and supporting girls' continued education as capital expenditure instead of pure social spending. This would help align fiscal frameworks with longer term growth targets.

Ending child marriage practice will not, on its own, ensure that Africa will reach its development goals. However, unless addressed, this structural barrier will continue to hamper productivity, competitiveness, and the delivery of the Agenda 2063. Recognizing that ending child marriage is an economic as much as social imperative would be an important step forward. It would also place the girls’ empowerment where it belongs: at the center of Africa’s development strategy and its pursuit of inclusive and sustainable growth.

[1] United Nations Population Division data (2022).

[2] World Bank (2025), Pathways to Prosperity for Adolescent Girls in Africa: Pathways to Prosperity for Adolescent Girls in Africa

[3] Yeboua (2024), Get gender equality right in Africa, and prosperity will follow, Institute for Strategic Studies: Get gender equality right in Africa, and prosperity will follow | ISS Africa .