by Aboubakri Diaw * and Stephen Chundama*

Introduction

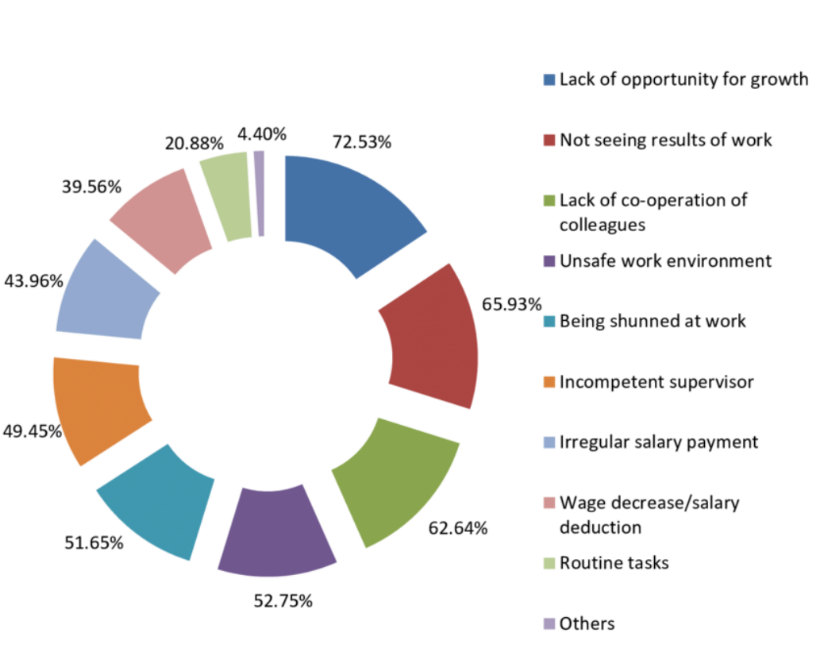

It is widely accepted that the success and failure of any organization is contingent on the motivation, skill and welfare of its human resources, among others. According to Adetipe (2020), the lack of growth opportunities, the absence of results from work done, and a lack of cooperation from colleagues are the leading factors contributing to staff demotivation.

During my humble service in numerous organizations, I have often been appointed to lead teams that were characterized by low morale, eroded trust, and virtual collapse of cross-sectional collaboration. These teams had been paralyzed by personal tensions among all categories of staff, such as between managers, supervisors and supervisees, researchers and “others”. A common feature among them is a lack of strategic clarity and deep disengagement among junior staff.

The teams I inherited were often scarred by years of dysfunction, fractured communication between units and sections, overlapping mandates, personality-driven conflicts at senior levels, and a culture in which younger or junior staff felt invisible. These situations often occurred alongside observable stagnation or retrogression of performance indicators.

My correction of such situations, through sustainable internal transformations, was neither accidental nor driven by top-down directives. From my personal experience, it was achieved through Restorative Leadership[1] (RL) – a leadership approach that combines listening, humility, structure, and inclusivity.

Therefore, this piece proposes RL as a replicable leadership model for organizational turnarounds using insights from my adaptation of a leadership approach that has evolved through practice and experience; proven to work using the organizations I have worked for, as case studies; and is strongly grounded in a growing body of evidence on psychological safety, humble inquiry, and adaptive leadership.

Step-by-step approach to restorative leadership

1. Listening as an entry point

Schein (2014) provides evidence that listening—not auditing or instructing, is the most strategic form of inquiry a leader can deploy. I adapted this approach by undertaking deep listening through one-on-one informal sessions with staff[2], which revealed recurring patterns of exclusion, unresolved personality-driven conflicts, and distrust—insights that are invisible in formal reporting lines.

2. Creating safety and trust

Secondly, it is important to acknowledge the failures of past leadership in a general way, then invite everyone to co-develop behavioral norms, including civility in meetings, transparency in communication, and respectful disagreement. Reinforcement and progress in adherence to norms were tracked daily through a literal open-door policy. These and other small, symbolic practices helped to restore psychological safety and provide reassurance that direct and indirect victimization[3] of staff who openly express their honest opinions will not occur.

3. Co-creating vision and purpose

Rather than drafting new strategies behind closed doors, I utilized the Appreciative Inquiry method, developed by Cooperrider & Srivastva (1987), by facilitating joint planning sessions involving cross-sectional teams, including early-career professionals. The Deci & Ryan’s (2000) self-determination theory argues that developing such autonomy and ownership is crucial for intrinsic motivation.

4. Structural realignment and transparency

To reinforce alignment and efficiency, I often undertook a light-touch reorganization, where: overlapping roles were merged; specific and rare expertise was shared; and decision-making authority was clarified using a RACI matrix. This transparent and systematic realignment of workflows reduced ambiguity and enhanced shared accountability, in line with the transparency principles developed by Lencioni (2002).

5. Mediation and valuing diverse contributions

One of the more difficult aspects of adapting the RL process involves mediating deep personal conflicts among senior managers and/or between them and their teams. To effectively resolve these conflicts, I often introduced short, interest-based mediation sessions inspired by Fisher and Ury’s (1991) model of principled negotiation. These sessions created a safe environment for sharing deeply rooted grievances and identifying shared goals. Simultaneously, I introduced a regular “kudos round” where staff publicly acknowledged each other’s contributions. Unsurprisingly, junior staff—once sidelined—were increasingly recognized for their insights and commitment, as predicted by Cameron (2012).

6. Fusion squads and cross-sectional work

To disrupt siloed working habits, I launched small, time-bound “fusion squads[4]” of cross-sectional staff, with assigned tasks such as clearing backlogs, improving reporting, disrupting thinking or solving practical process issues. In accordance with Hackman’s (2002) criteria for real teams, these structures or taskforces created interdependence, learning opportunities, and visible markers of staff engagement.

7. Feedback and adaptation

During periodic meetings, I conducted short, pulse surveys to assess trust, workload fairness, clarity of purpose, and perceptions of inclusivity. Results were openly shared during plenary sessions and used to inform adjustments. This iterative practice[5] echoes Heifetz’s (1994) adaptive leadership model that proposes three broad steps, namely: observe, interpret, then intervene.

8. Embedding Culture and Sustaining Change

To ensure that progress was sustainable, we institutionalized key routines, such as: open-door access, kudos rounds, squad structures, feedback loops, and transparent workflows. A rotating "culture steward" was appointed to sustain the behavioral norms we had built. As Ahn et al. (2004) observed, many turnarounds collapse due to a lack of cultural embedding—so this intervention helped to mitigate this risk.

Conclusion: towards a replicable model

RL integrates emotional intelligence with structural reform. Trust was not built by slogans, but by daily acts of transparency, recognition, and collaborative work.

Following my detailed exposition of my experience in the use of RL over the years, and the success I have achieved by using it, particularly the restoration of teams into vibrant, motivated, efficient, and collaborative groups, four insights stand out. Firstly, distrust is as much an information deficit as an ethical one. When decision rationales and resource flows become transparent, suspicion dissipates. Secondly, humility is not performative self-effacement[6] but a gateway to richer information. By admitting gaps, leaders obtain uncensored realities that enable better decisions. Thirdly, enfranchising junior voices is not merely unselfish, but diversifies the cognitive toolkit with frontline intelligence that senior leaders often lack. Fourthly, structural redesign must accompany emotional repair. Without fusion squads, mediation protocols and visible workflows, renewed goodwill would have remained rhetorical.

A growing body of evidence suggests that “soft” interventions proposed by RL (e.g. appreciative inquiry and open-door access), reach full potency when married to “hard” mechanisms that lock new behaviours into the fabric of daily work.

RL is not only replicable, but urgently needed in times of institutional uncertainty.

*Aboubakri Diaw is the Chief of Staff at the ECA

*Stephen Chundama is an Economist in the office of the Executive Secretary, ECA.